I am looking for other forward-thinking adults with a global view to join me in learning Mandarin Chinese as quickly and efficiently as possible. I have coordinated a 90-day beginning workshop based on research suggesting what will optimize our learning. Legacy funds from my father will cover all of our expenses, including providing awards for achievements.

Update: The inaugural workshop in Blacksburg, Virginia, U.S.A. is in progress and will end October 31, 2022. Another workshop may be scheduled. Please contact Anne Giles if you are interested.

Why?

“[Mandarin Chinese is] one of the most geopolitically important languages in the twenty-first century.”

– Jing Tsu, Kingdom of Characters: The Language Revolution that Made China Modern, 2022

“The next 100 years of human history will likely be defined by three things: the environment, artificial intelligence (or something like it), and China – and China plays heavily in the first two.”

– Jeremy Goldkorn, SupChina, 2/4/22

Why adults?

The findings of neuroscience contradict the myth that second language learning is ineffectual in adulthood. In fact, the intricately, deeply and extensively networked mature adult human brain may be primed for second language acquisition, particularly Mandarin Chinese. For older brains – I am 63 – neuroscience backs second language acquisition as a potentially enhancing, improving, even restorative cognitive endeavor.

How?

We will follow a research-informed curriculum I have derived from doing extensive literature reviews on the theory and science of adult language learning, particularly of Mandarin Chinese. I have summarized my findings here and the syllabus is here.

“I am neither an Athenian, nor a Greek, but a citizen of the world.”

– attributed to Socrates by Plutarch

For whom?

- For up to 6 adults, 21 years and older, with little to no exposure to Mandarin Chinese.

- Those interested in local and global business, academics, politics, and/or communities.

- Able, willing, and determined to prioritize the learning of Mandarin Chinese for 90 days.

- Able to allocate one hour per day to independent study for 90 days.

- Able and willing to attend these meetings:

– Once per week, 90-minute, in-person workshop, held in Blacksburg, Virginia, on Tuesdays, 3:00 – 4:30 PM U.S. Eastern Time. (Note: The workshop is designed to include this weekly, in-person meeting. Sorry, but if you cannot attend in-person meetings in Blacksburg, Virginia, please do not apply.)

– Once per week, 30-minute, online conversation group, Mondays, 1:00 – 1:30 PM U.S. Eastern Time, facilitated by Benfang Wang. - Access to a laptop or desktop, a mobile device, and a high-speed internet connection.

- Sufficient proficiency in English to read directions written in English.

- Desire to gain proficiency in Mandarin Chinese optimally. “Optimally” is defined as “as quickly and efficiently as possible, with the least amount of time, effort, and expense as possible.”

- Desire to gain proficiency in Mandarin Chinese in order to communicate on a meaningful level with speakers of Mandarin Chinese. “Meaningful” is defined as “the ability to speak, listen, write, think, feel, work, relate, collaborate, and connect in Mandarin Chinese.”

- Willingness to accept the designated, longer-term measure of the effectiveness of the workshop’s protocol as scores on the Mandarin Chinese proficiency exams administered by the Chinese government, the Hànyǔ Shuǐpíng Kǎoshì 汉语水平考试 (HSK).

Why the HSK exams?

The internationally-recognized, standard measure of proficiency in Mandarin Chinese is passing scores on a set of exams administered by the Chinese government, the Hànyǔ Shuǐpíng Kǎoshì 汉语水平考试 (HSK). Abbreviated “HSK,” passing the pre-2021 HSK Level 3 exam is considered the minimum level of proficiency for many employment and educational opportunities in the U.S., in China, and in other countries. (A recent Indeed.com job search using the term “Mandarin Chinese” produced 11,517 results in the U.S.) Passing the pre-2021 HSK Level 3 exam requires the ability to hear Mandarin Chinese and understand it, and to read and write it. Speaking is evaluated on higher levels of the HSK exam but not Level 3.

How much?

There is no fee for this workshop.

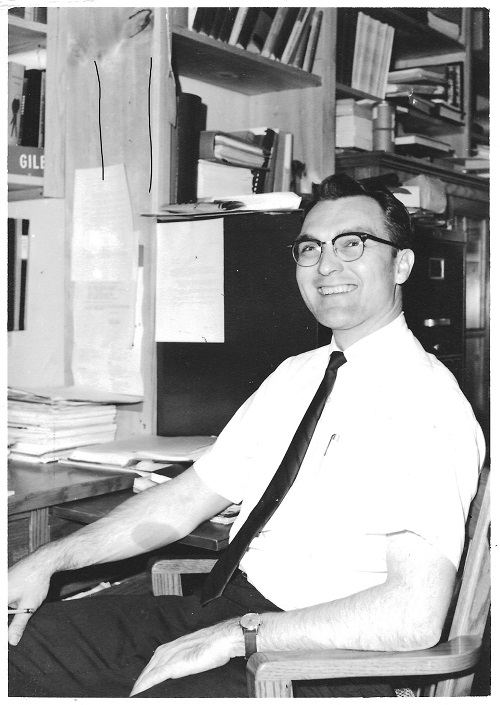

The Mandarin Chinese Workshop is funded through the legacy of Robert H. Giles, Jr., Ph.D., Professor Emeritus, Virginia Tech, to foster use of the findings of science to build a system of global, humane, human connection in service to the greater good. Ut Prosim.

Here is the proposed funding for the project. (.pdf opens in new tab)

What is provided?

- 90-day subscriptions to all paid online media and tools used in the workshop.

- Weekly, 30-minute, online conversation group, facilitated by Benfang Wang.

- Weekly, 30-minute, in-person group instruction with a native speaker.

- $100 funding for online instruction via italki.

- $50 award for submitting achievement scores after completing 30 consecutive days of study, one hour per day.

- $100 award for completing daily check-ins and submitting achievement scores after completing 60 consecutive days of study, one hour per day.

- $200 award for completing daily check-ins and submitting achievement scores after completing 90 days of study, one hour per day.

- Cash awards for achieving milestones. For milestones and amounts, please see the syllabus.

What is expected?

- Ability to attend in-person and online meetings as described above. Although residing in the Blacksburg area is preferred in hopes of fostering development of a post-workshop community of Mandarin Chinese learners and a “study buddy” cohort, workshop members may reside in other cities, states, or nations and commute to in-person meetings.

- 90 consecutive days of study, verified by daily check-ins.

- Submission of achievement scores in these 5 time increments: with application, pre-test/first day, 30 days, 60 days, post-test/90 days.

- Completion of Mandarin Blueprint’s 6-hour Pronunciation Mastery course within the first 14 days.

- Willingness to share scores with group members.

- Willingness to teach and learn, i.e. make presentations to group members about what they are learning.

- Willingness to follow group sharing protocols during meetings. This includes, when making a suggestion, differentiating between anecdotal, case study data and empirical research data and identifying opinions or theories as such.

- Congeniality.

Caveats

This project is an attempt to use the findings of research, plus logic and experimentation, to contribute to discovering aspects of the realities of learning Mandarin Chinese that optimize that learning for most adults, most of the time, better than other ways, and better than doing nothing. No less than fostering connection and understanding among the world’s people is part of the mission of this project.

- This curriculum is informed by current research but has not been tested by research methods.

- Although desired outcomes are hoped for, zero desired outcomes may result and no guarantee is implied.

If you have interest in the workshop

- Take and record your answers to the Mandarin Chinese Interest Survey.

If, after studying your answers to the Mandarin Chinese Interest Survey, you would like to apply to become a member of the workshop

Please open an email to send to me (contact info is here) and include this information

- Name and age.

- Phone number.

- Your answers to the Mandarin Chinese Interest Survey.

- An attachment of the .pdf of the page reporting your HSKlevel scores using Simplified Characters. HSKlevel is a 60-item assessment created using an artificial intelligence algorithm by François-Pierre Paty, a French Ph.D. student. (To create a .pdf of the page from a laptop or desktop computer, go to Print, then Destination, then toggle from the name of your printer to Save as PDF.)

- Date you took the HSKlevel assessment.

- A one- to two-sentence statement about why you want to join the workshop (maximum of two sentences).

- A one- to two-sentence statement about what you think you can contribute to fostering connection, collaboration, synergy, and optimal learning among the workshop’s members (maximum of two sentences).

- A brief acknowledgement that you have read the Statement of Intentions.

- How you heard about the workshop.

- Whether or not you have a Netflix account.

- Day of the week most convenient for you to attend an afternoon workshop meeting at a location in Blacksburg from 3:00 to 4:30 PM.

Send your application email to me as soon as possible.

Note: The first session of the Mandarin Chinese Workshop has begun.

With regard to this project, here are my disclosures.

If you are a native speaker of Mandarin Chinese residing in the Blacksburg, Virginia area and are interested in serving as a 30-minute, in-person guest instructor for a fee of $50 during one of our weekly group meetings, please read the job description then contact me.

About the workshop coordinator

Anne Giles, M.A., M.S., L.P.C., is a Licensed Professional Counselor in the Commonwealth of Virginia, U.S.A., and a student of Mandarin Chinese. She has passed the HSK 1 and HSK 2 exams. She holds master’s degrees in curriculum and instruction and mental health counseling, and a Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL) certificate. As an undergraduate at Virginia Tech, she studied Chinese history. She took one semester of Mandarin Chinese at the University of Connecticut in 1981. She attended the virtual National Chinese Language Conference in 2021 and 2022. She has taught English at the middle school, high school, and college levels.

Questions? Please contact Anne.

Image credit: iStock

Mandarin Chinese Workshop-related links

- Mandarin Chinese interest survey

- Workshop description (this post)

- Workshop syllabus

- Workshop schedule

Note: According to Hsueh-Chao and Marcella Hu (2013), “Previous studies examining the effect of word frequency on vocabulary learning demonstrated different results, ranging from 3 to 17 exposures for acquisition of varied aspects of word knowledge to take place.” (The Effects of Word Frequency and Contextual Types on Vocabulary Acquisition from Extensive Reading: A Case Study. Hsueh-chao Marcella Hu, Journal of Language Teaching and Research, Volume 4, Number 3, May 2013)

Last updated 2023-02-22

All content on this site is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical, professional, and/or legal advice. Consult a qualified professional for personalized medical, professional, and legal advice.