I cried when I read Nora Volkow’s state-of-the-science essay on addiction last month. Volkow’s heroic attempt to define the wicked complexity of addiction is probably still too technical and too long for most mainstream readers – much of it for me as well – but I’ve reread and studied and pondered. Of all the research I’ve seen, Volkow’s explanation most closely matches my own experience with addiction.

I wrote a brief commentary on her essay exactly one month ago today and included excerpts. Since then, I’ve followed every English teacher’s guidance – and my own when I was one – to allow the mental act of paraphrasing, as Purdue puts it, help me “grasp the full meaning of the original” by putting it into my own words.

I wrote a brief commentary on her essay exactly one month ago today and included excerpts. Since then, I’ve followed every English teacher’s guidance – and my own when I was one – to allow the mental act of paraphrasing, as Purdue puts it, help me “grasp the full meaning of the original” by putting it into my own words.

So, here is my paraphrase of Volkow, applied to express what it’s like to be Anne, addicted:

In 2006, I was just being Anne, just drinking wine in the evenings, and then something turned and I couldn’t stop drinking. Somehow – and I don’t know how – I was able to begin to abstain in 2012. A world, no, a universe of misery unfolded.

No matter how hard I try, I can’t feel much pleasure. I think I remember delighting in orange leaves in the fall, but I’m not sure. I am now highly sensitized to pain, physical and emotional. A back spasm sends me to a neurologist, not for a hot pack. I couldn’t find the serial number on the modem, burst into tears, and only the randomly kind words of a woman in tech support at the cable company got me connected enough to myself to get me connected back to the Internet.

I go down faster and farther, and when I get down, my compromised ability to feel pleasure makes it miserably hard for me to get back up. I am conditioned like Pavlov’s salivating dog to turn to the substance to which my brain turned for release from the incarcerating hell of that intractable, unrelenting down-ness.

And my poor punkin head – my prefrontal cortex – took a hit to its decision-making ability. I might notice an urge but be unable to resist it. I may make a plan but not stick to it. I used to run a company and now I can’t even run my own intentions.

In sum, I am under-sensitized to pleasure, over-sensitized to pain, automated to use my substance to feel normal, and can’t do much about changing any of it because I’m no longer that great at deciding something or sticking with it even if I do.

People suffering from addictions are not morally weak; they suffer a disease that has compromised something that the rest of us take for granted: the ability to exert will and follow through with it.

– Nora D. Volkow, M.D, quoted in What We Take for Granted

In her brilliant, definitive, 2,600-word essay, Volkow offers one sentence about treatment: “Restoring normal balance between reward, anti-reward, and executive systems in the brain may require behavioral interventions and, when they are available, medications.”

“May.” May.

What a bright, bold light Volkow shines on what and why addiction is! How uncertain we are what to do about it!

In her essay, Volkow doesn’t include discussion of the confounding factor that I, like so many others who suffer from addiction, have co-occurring mental illness that snarls and intertwines with addiction. The inner experience of addiction and mental illness, truly, make it almost impossible to feel human or to feel part of humanity.

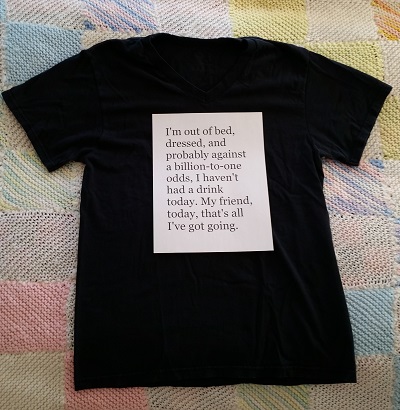

I’ve heard there’s a t-shirt with the slogan, “I’m out of bed and dressed. What more do you want?” Maybe I want one that says, “I’m out of bed, dressed, and probably against a billion-to-one odds, I haven’t had a drink today. My friend, today, that’s all I’ve got going.”

Online Advertising

What It