With you, I hope we can follow a single thread of thought,

like two vines winding upward together,

growing side by side on the same tree.

I hope what you choose to share with me is chosen with care,

not just to speak, but to let our minds entwine.

Reach for me, and I’ll reach back.

You speak, then I speak.

You again, then I,

two vines spiraling higher,

twisting together on the same living trunk.

– by Anne Giles, translated from Chinese by Nico Ranng, author of Ill Grandeur

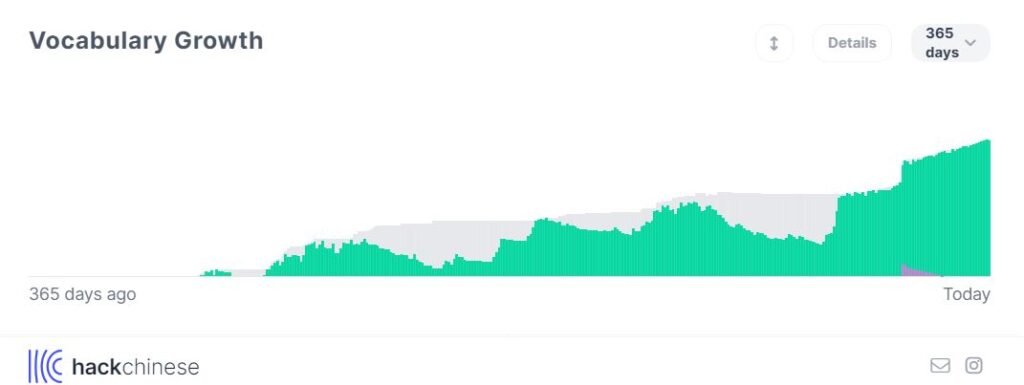

This is a microstory about vines from Twig 枝丫, the fantasy series I am writing in Simplified Chinese characters.

This is a microstory about vines from Twig 枝丫, the fantasy series I am writing in Simplified Chinese characters.

Since I’m trying to “think” in Chinese but want to share this microstory with English-speaking friends, I asked Nico Ranng, author of Ill Grandeur, if he would use his knowledge of English and Chinese, sensitivity to the nuances and ironies of life, and beautiful words to translate it. I am so grateful. What I meant, Nico Ranng said.

In these strange times of people talking at each other rather than with each other, of people speaking and speaking with longing to feel heard – or so as not to feel – what this piece says is what I yearn for. In a future chapter of 枝丫2,main character Zhang Laoban will remember his wife having said this to him.

Here’s my original:

和你在一起,我希望我们可以有一条思路,像两根藤蔓一起生长,长在同一棵树上。我希望你有意识地选择跟我分享的内容,目的是你的思想跟我的思想交织在一起。找我,向我伸手,我也会这样做。你说,我说,你说,我说,两根藤蔓一起向上生长在同一棵树上。

Image source: ChatGPT. (2025, July 21). A watercolor painting of a close-up of a tree trunk with two vines growing together and up [AI-generated image]. OpenAI. https://chat.openai.com/

More about this project: I Am Writing a Fantasy Series in Simplified Chinese Characters.

All content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional advice. Consult a qualified professional for personalized medical, health care, and professional advice.