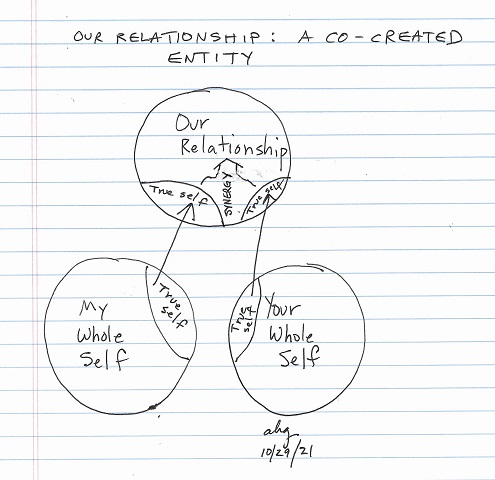

Consider the following formulation for creating new possibilities for effective relationships, particularly partner relationships.

One person and another person. Each person is a separate, self-aware entity, a whole self, comprised of a true self, a personal history, and beliefs held about relationships taught by family, culture, and the media.

Each person is responsible for identifying and stewarding their own needs, wants, preferences, strengths, values, and priorities and discovering and discarding unhelpful beliefs about relationships.

The relationship. Each person contributes a portion of his/her/their whole self – ideally components of the true self – to mutually co-create a third entity, the relationship. Instead of attempting to shape or transform (or force) oneself or the other to meld personhoods into oneness, the contributions of each work together in synergy to create a novel, separate relationship that enriches each and both.

(Pronoun for both singular and plural, used hereinafter, is they/them.)

Inputs. Each person attempts to add to the relationship what helps it, not hurts it. Each person self-monitors what they contribute to the relationship.

Conflict. Conflict naturally arises from difference. To both protect and foster the co-created third entity – the relationship – each person maintains awareness of self, other, and the relationship, and speaks up when something is awry.

Negotiation. The purpose of negotiation is to – in mutual, well-intentioned synergy – decide what inputs each person can add or remove to protect and foster the relationship. Each person focuses on themselves and their experience of the relationship, rather than on fault-finding or blaming. (Each person’s insufficient self-awareness or relationship-awareness can often be sources of unhelpful inputs to the relationship.) Rather than “working on the relationship,” each person works to become aware of their own helpful and unhelpful inputs to the relationship.

In a relationship where both partners seek and practice self-awareness, sentences using “I” would often outnumber sentences using “you.”

Sources of conflict

Imposition of unconscious, unexamined beliefs about how self, others, and relationships are or should be is a primary source of conflict in relationships. Beliefs can be held so strongly that they are perceived as facts.

(The “power of love” to change people is a common belief in many cultures. Another one is, “They should know what I’m feeling or thinking without me having to tell them.” If we do the numbers on the human condition, particularly on the human brain, we pretty much don’t stand a chance. If we don’t tell them, the odds are enormous that they don’t know.)

Attempts to control or change the other person – to attempt to make them 1) do what is desired, or 2) not do what activates anxiety or fears – is a source of conflict in relationships.

Expectations – non-negotiated, unspoken, and/or mismatched – about the frequency, duration, and method of contact are another source of conflict in relationships.

Unilateral decision-making is a leading cause of relationship discord. Unilateral decision-making is the act of making a decision – the results of which might impact the other person – without, at minimum, prior notice, or, optimally, prior negotiation to increase probabilities of maximizing benefits and minimizing costs for both parties and the relationship.

Unilateral decision-making by one person often activates intense feelings and either-or thinking in the other person. Although perhaps not intended, statements such as these may be implied or perceived:

- “My priorities are more important than your priorities.”

- If I “didn’t think to tell you,” “forgot” to tell you, ghosted you, or no-showed: “You are forgettable and non-important.”

- If I was “afraid to tell you”: “I avoided telling you the truth because my concern for my feeling of fear weighs more heavily than my concern for any troubled feelings you might have.”

- “You can count on me as long as what you want from me is what I want to do.”

- “I care for you less than you care for me.”

- “I have more power in this relationship than you do.”

- “Although we have a spoken or unspoken contract, it’s okay for me to breach it and not say or do as I promised because my needs and wants come first.”

- “It is all about me.”

What the other person may feel, think, and do as a result of learning of, or experiencing the making of a unilateral decision:

- Primary feelings: sad, afraid, mad, surprised

- Secondary feelings: feeling hurt, overwhelmed, disoriented, discounted, de-identified, de-prioritized, devalued, betrayed, used/misused, excluded, deprived, full of rage, resentful, unsafe, doubtful, wary, humiliated, lonely

- Actions: withdrawing, withholding, and shutting down; accusing and criticizing; moving from active, to passive, to indifferent; contemplating exiting the relationship and/or enduring it for reasons other than regard.

- (Primary and secondary feelings are defined in this glossary.)

Why one person may make a unilateral decision without informing the other

- The subject is within the person’s rights to make a solo decision.

- The subject was new to both parties’ awareness and had not been discussed or negotiated.

- In a relationship where people are attempting to change or control the other person – rather than mutually negotiate a relationship – the subject may have been avoided to avoid the other person’s objections or counter-control efforts.

- Deficits in self-awareness and relationship-awareness, unacknowledged disinterest, or intention to hurt may result in unilateral decision-making.

Caveat: Regardless of the reason, unilateral decision-making can be a dealbreaker for relationships. Some relationship thinkers posit the existence of a relationship “bank account.” A single withdrawal that results in a significant sense of unsafety, distrust, or non-mutual power-sharing may require manifold deposits to replace.

To address conflict

- Approach reality and acknowledge the data.

- Are both parties able to agree on what constitutes data, facts, and reality? Is there an attempt to convince, contest, or defend? Since a relationship is based on mutual understanding, further progress may be unlikely.

- For pain caused by insensitivity, apologize.

- Examine intentions. Does each person have the best intentions for the other, regardless of whether or not the relationship exists? What is the purpose of each person’s engagement in the relationship?

- Examine outcomes. Is synergy occurring? Does each person, for the most part, experience their personhoods and lives enriched by engagement in the relationship?

- Attempt to mutually negotiate next steps.

Of possible interest

In addition to other sources, the above text is informed by cognitive theory, the concept of dialectical synergy born of “Opposites can both be true,” a concept central to dialectical behavior therapy, invented by Marsha Linehan, Ph.D., work by the Gottmans, and relational self-awareness theory, formulated by Alexandra Solomon, Ph.D. The accompanying hand-drawn diagram is adapted from Alexandra Solomon’s “My Stuff + Your Stuff = Our Stuff” slide from her training Loving Bravely: Helping Clients Who are Single, Dating, & Single-Again.

This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical or professional advice. Consult a qualified health care professional for personalized medical and professional advice.