If you have assessed a situation and found no immediate threat, have followed advice from medical professionals, but still find yourself feeling a sense of panic, here may be a way to use cognitive therapy on your own behalf.

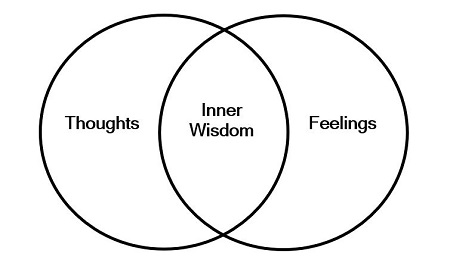

Panic is usually an inner state resulting from thoughts about believing one is helpless. Believing there’s no way out understandably causes what we’ll term the brain’s “feelings processes” to overpower the brain’s “thinking processes.” The antidote is to regain access to one’s ability to think, then to use both feeling and thinking processes to consider helpful possibilities. According to research by the Gottmans, regaining this ability takes about 20 minutes.

1. Say, “I am feeling panicked.”

Simply naming what you are truly feeling, whether to yourself or aloud, requires you to think, thus beginning the process of bringing your thinking “back online.” You activate your brain’s innate ability to work with reality by approaching it rather than avoiding it.

2. Move.

With the physical abilities you have, stand up, shift your posture, pick up an object, pat your pet.

Deciding what to do and doing it, again, activates the thinking processes of your brain.

3. Identify the thoughts you had prior to feeling panicked.

This, too, helpfully activates your thinking processes. Try to be as specific as possible. One thought is usually along the lines of “I feel helpless to __________.” Many thoughts may be in the form of “if-then” doom, i.e. “If ________, then it’s all going down!” Writing down your thoughts may offer additional clarity.

4. Challenge any thoughts that are “shoulds” with this fact: “I feel as I feel.”

The odds are good that feeling what you feel under the circumstances is legitimate. “I shouldn’t feel this way” is a belief that isn’t true. Further, thinking “I shouldn’t” deepens distress. Simply shift your attention away from any beliefs you hold about your feelings.

5. Imagine adjusting the volume knob on your inner state down a notch.

The brain has an innate ability to restore itself to stability. Simply becoming aware of one’s inner state eases it. Although one’s inner dialogue may be “I should/shouldn’t be feeling/thinking this way,” again, simply shift your attention to quieting the intensity of your inner experience.

6. Do all this with neither judgment nor rah-rah.

Unfortunately, the cure for thinking negatively is not positive thinking. Both require energy to sustain beliefs that may not be supported by facts. Reality is the groundwork upon which your brain primarily operates. Gently let the brain be real and do what it does.

7. Acknowledge that often beneath panic, sometimes at a nearly inaccessible level, is sorrow.

We feel so sad that things are as they are and that things have gone as they’ve gone. We may regret the past, ache for the present, and worry about the future. We may wish ardently that we could change things. Panic is often the brain’s way of putting distance between us and what we are so very, deeply sorry that we can’t change for ourselves, others, or our world.

8. Ask yourself, “What can I do to help myself with this?”

And there it is. By asking that question, you have accessed the very best of your feelings – your empathy and compassion for yourself – and the very best of your thinking – solving problems with facts. You can examine thoughts that have troubled you with your full humanity. In dialectical behavior therapy, the ability to access the synergy of one’s most skillful feeling and thinking is termed “Wise Mind.”

Giving oneself time to skillfully call forth one’s own inner wisdom can be the antidote to panic.

. . . . .

Image adapted from ” Mindfulness Handout 3: Wise Mind: States of Mind,” DBT Skills Training Handouts and Worksheets, Second Edition, by Marsha M. Linehan, 2015.

The content of this post is a synthesis by Anne Giles, M.A., M.S., L.P.C. of work in cognitive theory by Judith Beck, Ph.D., Marsha Linehan, Ph.D., Patricia Resick, Ph.D., Daniel J. Fox, Ph.D., and others.

This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical or professional advice. Consult a qualified health care professional for personalized medical and professional advice.